About Me

GANG OF ONE PHOTOGRAPHY

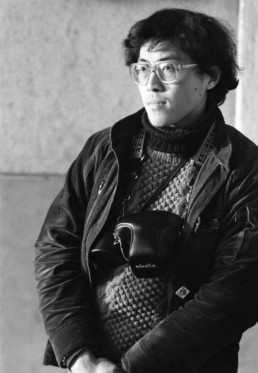

In 1981, with a second-hand camera and expired film, Wang Gangfeng王刚锋 set out to capture the everyday images of China that surrounded him. The scenes that he captured represent the daily ebbs and flows of life in China. A man reclining on a bamboo chair intently listening to his radio, a mischievous child holding the tail of a pig, or stream of multi-colored cyclists waiting in the rain are only a few of these unforgettable images he has produced during his career.

Before he became a successful photographer, like many others of his generation, he worked as a laborer. During this difficult time his desire to capture images of China began to develop. Even though he could not afford a camera he would frame moments in his memory. A sea of young workers carrying baskets of mud. The wrinkles on the face of his grandmother. And from these memories would emerge Wang’s appreciation for finding the perfect moment to photograph.

As he continued to work in farms and factories across China his desire to become a photographer grew. Wang’s dream to become a photographer was sealed when he saw a former mentor at a factory retire to a harsh life. This would not be a path Wang would follow. His sister who was working in the city used her savings to purchase Gangfeng an Eastern camera from Tianjin. From this point forward he would put all his time and limited resources into his passion for photography.

The early years of his photographic career in China were devoted to mastering technique through self study. With no formal photography schools open he poured over whatever materials he could track down. A translated German photography manual tucked away in the Shanghai Library and photography magazines sent from Hong Kong became his guides. Like a diligent student he would study and absorb the information. Then spend countless hours refining his newly acquired technical knowledge.

The subjects of those first photos were the people who lived in his neighborhood. Wang would explore, catching street life, in only the way someone who lived and grew up in the neighborhood could. He was an insider looking in.

What makes his photos from this period so distinct is how Wang’s presence is so natural. The school children go about laughing without paying attention to the lens focused upon them. A street dentist continues to operate on a patient without pausing to note the camera capturing the moment. Photos such as these emphasize Wang’s vision of seeing the beauty of street life in China.

Success and recognition would come with the publication of his work in the People’s Daily. His photo of two twin sisters practicing Judo opened the door for more assignments and projects. Entertainingly, this first published photo was not credited to him as the editors had lost his name and address. Only after a cousin of his in Beijing recognized Gangfeng’s work and called him did he know that he had become a published photographer.

As he continued to sell his work and receive private commissions he was able to establish his Gang of One photography studio and thrive in this new environment. Over the next decade his work began to gain international attention. His work became recognized for its ability to document the diversity of the human experience in China. The prestigious Musee de l’Elysee in Switzerland selected 18 of his photos for their permanent collection. Photo Life magazine described him as one of the top 25 photographers. And of particular note, in 1991, was having his photo (Tending Buffalo) selected out of 12 000 other entries to win the Ballantine’s First International Photography Award(5000 Pounds in Cash).

Despite the current acceptance and appreciation of his work it was not without controversy. During the 80’s Chinese photographers focused upon traditional subjects like architecture or scenery. Wang’s work stood out for its honest depiction of everyday life. Some critics accused him of showing the dark side of China. His response to such comments was simple and direct. He explained that he wanted his viewers to look beyond the surface of his subject’s worn clothes or wrinkled skin. He wanted the viewer to appreciate the personal strength and inner beauty of his subjects.

In terms of the future Wang still plans to document his beloved homeland, and even other countries.

With his keen eye for finding the fleeting moment he will continue for many years to capture all the wonder and excitement.

王刚锋:来自中国最深处

王刚锋,中国第一位自由摄影师。40年来用独特的风格记录了中国的变化。他的作品既具有西方现代艺术的表现手法,又保留了中国民族传统的创作风格,在国际摄影界享有极高的声誉。加拿大最具权威的摄影《PHOTO LIFE》评选加拿大最杰出的二十五位摄影师之一,他是其中唯一的华人。1991年,他的一幅作品《孺子•牛》,在国际摄影大赛中最具规模和影响的英国“百龄坛”最佳摄影大赛中一举夺魁,奖金5000英镑现金,国际华人圈为之轰动。

如今定居上海的他,在为跨国企业拍摄商业项目的同时,从未停止过艺术的脚步。王刚锋与这个时代大部分人最大的不同是,不在所处的位置,而在所持的态度。读懂他的作品,你更能读懂这个时代。

□李汶徽 顾玉雪

“上山下乡”中的艺术原乡

记者面前的王刚锋,儒雅中有一种平实的力量,眼镜后的深沉双眸,两鬓的少许白发,正所谓“不见白头不是真风流”。当他用带有磁性的嗓音讲述他的摄影人生,你会发现一种如同加缪在《局外人》中赋予默尔索的气质,“坦诚、光明正大、拒绝矫饰自己的感情”!

这大概也是一个独立摄影师的灵魂所在,但他对于摄影的理想生发,却是来自于一个革命色彩主导一切的时代。

1975年,19岁的王刚锋从上海来到了崇明的一个农场,接受“上山下乡”再教育。

这年冬天挖河,一挖几个月,“就像埃及造金字塔的奴隶一样”,开河的壮观场面使王刚锋萌生了一种愿望——他想把一切记录下来。

6年面朝黄土背朝天的农场生涯,那副沉重的担子,不光磨出了王刚锋的“游子肩上芥”,也让他开始思考那个时代的一切—-他的心头之起“芥”。1981年,王刚锋回老家上海当起了钳工,一个月36块钱工资,一直入不敷出。后来在街头,他遇到了退休的师傅,正在人行道上摆摊,卖一卷卷的橡皮膏,他似乎看到了自己“一眼看得到头的人生”。

“自打在路上偶遇师傅后,我知道我该干嘛了。”王刚锋决心做庸常生活的反叛者,他所拿起的武器便是摄影。当时父母希望他参加高考,王刚锋却每天偷偷一个人躲到图书馆,把所有当时能找到的摄影和美学书籍背了个滚瓜烂熟。

他从不同的朋友那里借照相机,并配上过期的国产黑白胶卷练了起来。为了省钱,胶卷是应该在暗房里,用剪刀把盘片剪成一段一段的,然后装进胶卷盒子里。没有暗房,只能用三条大被子裹住手臂在里面装,手出汗了,没有空调电扇降温,妹妹和外婆用大蒲扇轮流对着王刚锋光着的脊背扇。

后来,妹妹拿出五六年的积蓄,给王刚锋买了他人生第一台相机—-一架价值100多元的东方牌相机,从此,大鹏展翅,他开始挎着相机,骑着自行车,在上海的大马路上、小弄堂里寻找灵感、捕捉生活。

一天,他游荡(只见他整天荡悠,而没有见到过作品,他的母亲担心地称他为“无业游民”)到上海外滩,只见人群中,一对双胞胎小姊妹正在父亲的监督下练习柔道,神态是那么生动可爱,加上围观群众紧张的表情,王刚锋便情不自禁地按下了快门。这张处女作后来发表在《人民日报》上,当时的编辑还弄丢了他的地址,只好给他署名“刘夏鸣”—-谐音“留下名”!后来他拿到了12元的人生第一次稿费,之后,他便一发不可收拾!

从“刘夏名”的草莽时期,王刚锋便发誓要做世界上最好的摄影师之一,口出狂言的同时,其实他那时甚至不知道摄影师是如何谋生的。于大多数人而言,谋生而后谋爱方是正道;于他而言,谋爱却最为珍贵!

第一位“走出去”的摄影师

上世纪八十年代末,摄影艺术已经重新焕发了生机,当时的主流是很多人都去拍名人、拍名山大川、拍重大事件、拍少数民族节日……,但王刚锋的审美是这样的:“生活,你把它美的那一面挖掘出来,变成一张人见人爱的照片,这才是本事,这也叫艺术!”

1982年,王刚锋背着相机来到了安徽凤阳采风,“凤阳是当时改革开放的第一站,艰辛的探索之后,曾经的人民公社差不多都解散了,牛、羊全都分给了农民去养;地分给了农民去种,让‘耕者有其田’”,王刚锋说道。

经历过文革的他,敏锐地感到了这种大时代的变化。他在凤阳当地找到了一个偏僻的却“及其上照”的村庄,并在一家农户住下来。“那艰苦条件就别提了,被子是硬的,像木板差不多,而且是臭的!冬天破茅屋太冷,我就把它们的窗用报纸糊起来”。

王刚锋白天不光自己搞创作,还为村民们拍肖像,以赚取回家的路费;晚上就用明矾把大缸里带泥沙的河水用明矾沉清,然后用来冲胶卷、印照片。第二天呢,送照片给“客户”、收费、再找新的客户拍肖像、搞创作……,日复一日,直到他感到“创作丰收了”,才打道回府。

李白当年“茅屋为秋风所破”而出名诗,如今似乎他也得到了茅屋之“精髓”:正是在凤阳,王刚锋拍下了对他至今影响至深的一张照片,他给它命名为《孺子•牛》。作品展示了这么一幅画面:一个牧童酣睡在一条醒着的牛身边,就像躺在母亲的怀抱里一样,意境如同一首人性的交响曲。事实上,在王刚锋的作品中,往往以农村老人和孩子为主角,从看似平淡的生活中汲取一幅幅色彩斑斓的风俗画。业内评价他“敢于直面人生,不回避人间的苦难,并用一种非常温柔的、同情的眼光注视着他周围的人和事,诉说着无限的人性之美。”

1990年,《孺子•牛》在国际摄影大赛中最具规模和影响、奖金最丰厚(五千英镑)的英国“百龄坛”国际摄影大赛中,击败了来自56个国家和地区的摄影高手所拍摄的近万张作品,一举夺魁,赢得了头等奖5000英镑!消息一传开,中英文报刊、摄影杂志和加拿大电视台先后为他制作了专题报导及节目。

此后,王刚锋一发不可收:1989年,他被加拿大蒙特利尔市政府邀请,在市政大厅举办了他的个人黑白影展;1994年,还被美国东部一所艺术院视觉系聘为荣誉教授;他的18幅作品被瑞士博物馆收藏,还被评选为25名加拿大最杰出的摄影师之一,之后,他便定居加拿大,从事广告摄影。作为中国第一位走出去的摄影家,王刚锋的大师格局已露峥嵘!

私人定制“家庭照”

1995年,为了挑战自己,王刚锋产生了把摄影棚开到纽约去的想法,“如果靠摄影能够在纽约生存下来,那么在全世界都能够生存下去”。去纽约之前,他先回上海探亲,没想到随着上海市场的开放,有西方经验的商业摄影师奇缺。这一回,所有人都拉着他要请他拍商业照,特别是外国公司。这让他发现了另一片谋生的土壤,于是乎,王刚锋带着14个箱子—-全部摄影设备,从加拿大毅然地回到了上海,以实现他的“中国梦”,而朋友们都说他“疯了”!

随着对外开放的加快,上海居住着许多来自欧美的家庭,他们大多是世界500 强企业派过来的高级管理人员,每年春末夏初,往往也是与公司合同到期的时候,老外们便开始找他了。他们中流传着一句名言:“没有其他方法比请摄影独行狭王刚锋拍一套家庭照,来对上海这个我们生活了多年的城市作别更好!”

于是,周一到周五,他忙着为外国公司拍商业照;而为这些生活在上海的外国家庭拍摄具有上海特色的全家福,便成了过去十多年里,王刚锋周末主要的工作。

但深入中国乃至世界各地的农村,拍摄底层民众简单生活中那快乐的一刻,仍然是他一直没有放弃的艺术理想。

正如他自己所说 “商业摄影只是我的‘面包和黄油’,只有真正的艺术创作,才是我的最爱”。从大凉山上的孩童,到南亚底层的民众;从上海弄堂的“隔壁邻居”,再到穿旗袍的美国家庭,画面多姿多彩,充满了创意和变化,但一直不变的是王刚锋那直抵人心的人文关怀,咱们有照为证!